The American women’s suffrage movement in early 1919

Victory was tantalizingly close. American women had been campaigning for the right to vote for 71 years, persisting despite entrenched opposition and many setbacks. Suffragist strategy had recently shifted to advocating for a national constitutional amendment when the state-by-state approach yielded limited results. Congress, however, stonewalled this fundamental women’s rights issue and President Woodrow Wilson initially refused to endorse it. Nevertheless, nationwide support for women’s suffrage was gaining momentum.

The 19th Amendment finally passed in the House in 1918, but failed in the Senate by two votes. In 1919, it again passed the House, but fell short by one vote in the Senate. After 71 years, the 19th Amendment was just one vote away from going to the states for ratification.

Why did suffragists picket at the Massachusetts State House on February 24, 1919?

Timing is everything. On February 10, 1919, the 19th Amendment had failed to pass the Senate by one vote. In less than a month, on March 4, 1919, Congress would adjourn. Suffragists did not have much time to convince one Senator to change his mind.

President Woodrow Wilson was returning home by ship after three months abroad at the Paris Peace Conference in the aftermath of the Great War (World War I). After some delays, his ship was due to arrive on February 24, 1919. Initial plans to land in New York City were abandoned when it was determined he would be met there by hostile demonstrators. Boston promised a warm welcome, including a parade.

Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party had a different welcome in mind. With only nine days now left before Congress adjourned, they wanted President Wilson’s support in passing the 19th Amendment in the Senate. They decided the most effective way to convey their message to the President was to picket in front of the Massachusetts State House, where his motorcade would pause.

What happened on February 24, 1919?

Click image to enlarge

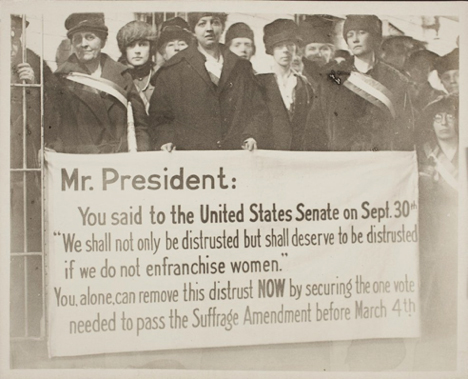

On the morning of February 24, 1919, twenty-two suffragists exited from 9 Park Street, the Boston headquarters of the National Woman’s Party. They marched around the corner onto Beacon Street, pushing through a line of sailors guarding the parade route for President Woodrow Wilson’s motorcade. They came to a halt in a long line outside the Massachusetts State House, directly in front of the governor’s reviewing stand filled with local dignitaries and 500 wounded veterans from the Great War. For forty-five minutes, they stood in silence as their purple, white and gold banners and a large banner with a message to President Wilson wafted in the breeze.

Tens of thousands of spectators thronged the streets of Boston to watch the Presidential motorcade pass. The streets along the parade route were lined with military and police as an attempted assassination of French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau on February 19 had heightened security concerns.

Suffragists had been picketing the White House for over two years, but this was the first and only time they picketed outside of Washington, DC. Alice Paul had informed the city of her intention to picket President Wilson. The National Woman’s Party also planned to have a demonstration on the Boston Common later that afternoon. The police had warned Alice Paul that anyone who protested in either location would be arrested.

Police Commissioner Curtis and Superintendent Crowley informed Alice Paul and the picketers that they had to leave before President Wilson’s motorcade arrived or face arrest. The picketers refused to move. The officers appealed to Alice Paul, who was standing to the side. She said they would carry out their plans. The suffragists were informed that if they did not leave in seven minutes, they would be arrested for loitering. They stood their ground, and after seven minutes, they were taken into custody. The only one to resist arrest was Betty Gram, a National Woman’s Party organizer. She struggled against being taken into custody, refusing to relinquish her banner. It took two officers to carry her to the paddy wagon. She waved her banner out the back of the wagon as they passed the National Woman’s Party headquarters on Park Street.

There was also a suffrage demonstration on the Boston Common that same afternoon at which suffragists spoke out against President Wilson and burned paper in lieu of burning the text of his speech. Three of them were arrested.

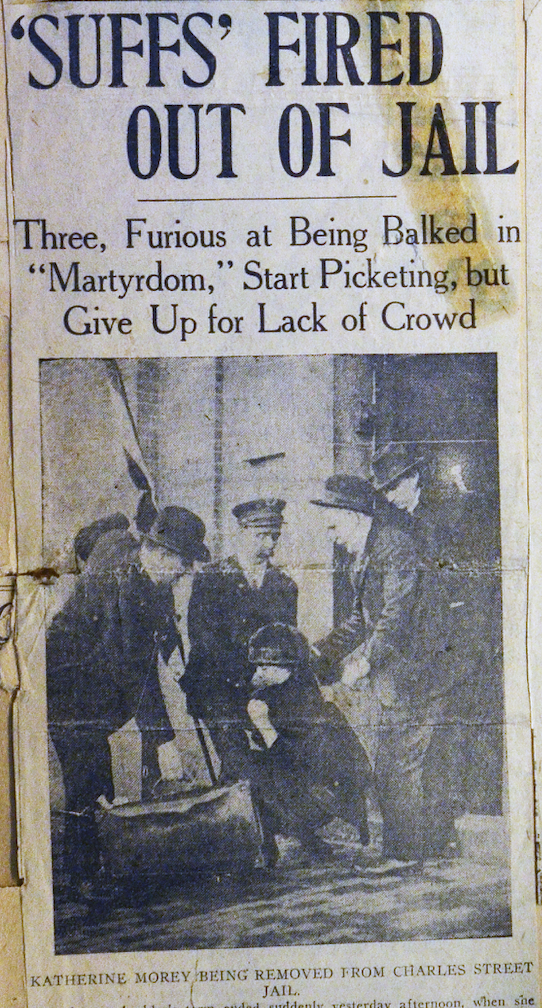

All the arrested suffragists spent the night in the House of Detention, and the next day appeared in court before Judge Bolster. Several women were released for various reasons. When the remaining sixteen women refused to cooperate, giving their names as Jane Doe or other false names, they were sentenced to eight days in the Charles Street Jail. The suffragists wished to serve their full jail sentence, as the excellent publicity they were receiving could help pressure President Wilson to take action on finding that one remaining Senate vote. But family members and a mysterious Mr. Howe kept paying their fines, which meant they were forced to leave jail. In the end, only one of the sixteen, Mrs. Rosa Roewer, was allowed to serve her full sentence, as her husband threatened legal action if she were released.

Was the picketing successful?

For a brief moment, it seemed as though the picketing had succeeded in turning the tide. Senator Gay came out in favor of the suffrage amendment shortly thereafter. But then the Senate prevented the 19th Amendment from coming to the floor for a vote before Congress adjourned on March 4, 1919. It was not until June that the amendment finally passed.

Why was picketing a controversial strategy?

The large and well-established National American Woman Suffrage Association, with its roots in the 19th century suffrage movement, entered the 20th century still hoping for a state-by-state legalization of suffrage. Although most Western states had indeed granted suffrage to women, Southern and Eastern states were stubbornly resistant. Alice Paul joined the National American organization in 1910 and advocated for working towards a national amendment instead. The ensuing controversy eventually led to her forming a breakaway group first called the Congressional Union, later named the National Woman’s Party. By 1915, Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American group, also reoriented their efforts towards passing a national amendment. The two suffrage groups, however, had very different styles. The National American took a nonconfrontational path, hoping to convince politicians through civil discourse and ladylike gentility.

Alice Paul, who had participated in suffrage protests in England, was willing to take a militant and activist approach, although as a birthright Quaker, she insisted that all actions be non-violent. When Congress and President Wilson stonewalled the 19th Amendment, National Woman’s Party suffragists began picketing the White House six days a week, starting in January, 1917. Their large banners would carry slogans such as, “Mr. President, how long must we wait for freedom?” No one had ever picketed the White House before.

Once the United States entered the Great War (World War One) in April, 1917, the National American group suspended their suffrage work and turned to supporting the war effort. Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party carried right on, arguing that women were being asked to support a war that they had no say in. This was not a popular position, and men began heckling their picketing lines, at times becoming violent. President Wilson’s administration also cracked down on dissident demonstrations, including suffragists, in order to present a united front to allies. Suffragists began to be sent to jail, and at times received very harsh treatment there. After the Great War ended, the National American organization resumed their efforts to win over Congress to support the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

By 1919, the two suffrage groups had a very acrimonious relationship, refusing to even speak to each other, to say nothing of coordinating strategy. The difference in their approaches is exemplified by how they behaved in Boston on February 24th, 1919. The National Woman’s Party suffragists took a stand in front of the State House, carrying the banner challenging President Wilson to find that one last Senate vote, daring the powers-that-be to arrest and jail them, in hopes that the ensuing publicity would work in favor of their cause.

In sharp contrast, members of the National American group presented Edith Wilson with flowers at the harbor pier. At the hotel, they met briefly with the President to thank him for his support of suffrage and working women, and later waved him off on the train to Washington, DC.